Multiverse Journal - Index Number 2222:, 12th July 2025, State's Monopoly on Violence is unLawful by it's own Actions and Laws

Journal across Realities, Time, Space, Soul-States.

—

July 12th, 2025

Good Saturday,

May the Spirit of the Gospel and the Holy Word be Always on our Tongues, in our Hearts, Minds, and in our Hands.

Holy Virgin Mother Mary and All Saints - Pray for us!

—

Index Number 2222:

— —

—

May this article find us all ever closer to God, and His Truth.

Here is a quick summary of the follow argument(s).

—

The modern democratic State claims the exclusive right to exercise legitimate violence within its jurisdiction. This monopoly, classically justified by social contract theory and the pursuit of justice, is contingent upon moral consistency, equal treatment under law, and impartial application of force.

This below paper argues that the State's long-standing sanctioning of abortion, combined with sex-based disparities in legal rights and access to lethal power, invalidates its claim to such a monopoly. Consequently, the State has forfeited its moral authority and constitutional legitimacy to act as sole wielder of force or moral arbiter in matters such as family law.

The argument is further extended to the domain of economic justice, where the State's protection and empowerment of corporations as "super-persons" with disproportionate rights and resources has rendered real, living persons—especially the poor and elderly—as vulnerable as the unborn, deprived of protection and recourse when essential services are denied or withdrawn.

—

Thank you in advance for your attention and any possible support to spread this argument to other for an opportunity in debates and considerations.

God Bless., Steven

PS. Added to bottom, 28th August 2025; Bishop Office Review, Google Gemini’s review and comments.

Here is an AI generated audio overview of this argument(s).

URL: https://notebooklm.google.com/notebook/0a0572a6-8c54-4bbf-a3eb-829aae5e81e4/audio

Title: The Illegitimacy of the Modern State's Monopoly on Violence: A Constitutional Critique

Abstract: The modern democratic State claims the exclusive right to exercise legitimate violence within its jurisdiction. This monopoly, classically justified by social contract theory and the pursuit of justice, is contingent upon moral consistency, equal treatment under law, and impartial application of force. This paper argues that the State's long-standing sanctioning of abortion, combined with sex-based disparities in legal rights and access to lethal power, invalidates its claim to such a monopoly. Consequently, the State has forfeited its moral authority and constitutional legitimacy to act as sole wielder of force or moral arbiter in matters such as family law. The argument is further extended to the domain of economic justice, where the State's protection and empowerment of corporations as "super-persons" with disproportionate rights and resources has rendered real, living persons—especially the poor and elderly—as vulnerable as the unborn, deprived of protection and recourse when essential services are denied or withdrawn.

I. Introduction

The concept of the State's monopoly on violence, as articulated by Max Weber and enshrined implicitly in modern constitutional democracies, presumes a foundation of moral restraint and universal justice. It is this presumed integrity that justifies the State's exclusive power to enforce laws, exact punishment, and override private force.

However, when the State uses this monopoly to permit or even promote private acts of lethal violence without public scrutiny or legal process—such as through the legalization of abortion—it contradicts its own foundational principles. Moreover, when it does so in a sex-discriminatory manner, denying men equivalent legal rights or moral standing, it violates the equal protection guarantees of constitutional law.

II. The Constitutional Basis of State Force

Modern constitutions, including that of the United States, presume that government power is derived from the people and constrained by rule of law. The Fourth, Fifth, and Fourteenth Amendments in particular provide for due process, equal protection, and the sanctity of life and liberty.

The State's power to use force, whether through law enforcement, war powers, or judicial punishment, is tightly bound to procedural safeguards. This principle extends to protection of life: the government cannot deprive persons of life without due process of law.

Yet abortion, as currently practiced, is an extra-judicial act of intentional killing authorized by the State, with no trial, hearing, or burden of justification beyond the private desire of one party.

III. Abortion and the Delegation of Lethal Force

Since Roe v. Wade (1973) and especially under Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992), the U.S. legal framework has granted women the ability to authorize the termination of a developing life within their wombs. This delegation of lethal force is:

Not constrained by due process

Not overseen by neutral public authority

Not subject to cross-examination or opposing argument

Thus, the State has contracted out its power of life and death to a private individual, based on subjective reasoning, sex-based status, and with no reciprocal rights for the father. This is inconsistent with any constitutional vision of ordered liberty or equal justice.

IV. Sex-Based Disparity and Legal Incoherence

The legal right to abortion is not universally available to both sexes. Only women may exercise this lethal discretion; men are excluded categorically.

This creates two systems of law:

One in which women are sovereigns over life and death of their offspring

Another in which men have no comparable recourse, standing, or authority

This disparity contradicts the 14th Amendment, which guarantees equal protection of the laws to all persons. No just State can claim legitimacy while authorizing violence for one class and denying equal redress or moral standing to another.

V. Consequences for the State's Monopoly on Force

By permitting one class of citizen to kill at will, the State has:

Abdicated its exclusive claim to regulate violence

Undermined the universality of its law

Betrayed its obligation to protect life impartially

Furthermore, by enforcing this system selectively—e.g., prosecuting private violence by men, but ignoring lethal acts by women under the abortion regime—the State weaponizes its monopoly politically, not morally.

Such a government cannot be trusted to wield force justly, nor to determine when violence is warranted. The monopoly, once predicated on reason and justice, now functions arbitrarily and discriminatorily.

VI. Motion for Judicial Redress: The Father's Right to Protect Life

Given the moral and legal incoherence demonstrated above, it follows that the State cannot claim a just and exclusive monopoly on violence in matters where it has abandoned its duty to protect innocent life, specifically that of the unborn.

A father, under both Natural Law and civil duty, possesses a right, obligation, and moral imperative to protect his offspring from unjust harm or death. When the State sanctions the killing of unborn children without offering the father legal standing, redress, or protective authority, it becomes complicit in an injustice that transcends mere procedural failure.

No legitimate State may criminalize a father’s resistance to the destruction of his unborn child while simultaneously refusing him access to lawful protection of that child. The State, having permitted and protected a one-sided power of life and death, has relinquished its claim to be the sole moral and legal authority over protective force.

Therefore, this court must recognize:

That the State’s authorization of abortion violates Natural Law, due process, and equal protection.

That a father’s duty to protect his unborn child is an inalienable right rooted in nature and affirmed by civil society’s foundational ethics.

That any use of State violence—whether through law enforcement or judicial punishment—against a father exercising this duty is illegitimate.

That the State must not only permit but actively support the father in fulfilling this obligation to protect his child from unjust harm, including from abortion.

Until the law is corrected to affirm this natural and constitutional duty, the father’s obligation stands above unjust statutes and bureaucratic fiat. The State must either reform itself to protect all life equally or surrender its pretension to moral and legal supremacy in matters of life and family.

VII. Motion for Judicial Redress: The Public Duty to Protect Life

Where the father is unable, unaware, or obstructed from fulfilling his natural and civil duty to protect his unborn child from death by abortion, the duty devolves to the broader community under Natural Law and moral obligation.

Any adult who becomes aware that an unborn child is at risk of imminent abortion, and who takes upon themselves the role of protector in place of the father, should be granted the same legal and moral standing as the father in this matter.

This surrogate protector acts not from personal claim but from a universal duty to defend innocent life from unjust killing. Such action is consistent with the principles of parens patriae when the State fails to protect the vulnerable.

Accordingly, this court must recognize:

That any morally aware and willing adult may exercise the father's duty when the father cannot.

That the State has an obligation to protect and support such individuals in preventing the death of an unborn child.

That it is unconstitutional and unjust for the State to penalize or use violence against such persons who act lawfully and morally to defend innocent life.

That the State must provide legal recognition, immunity from prosecution, and material support to those who intervene to stop abortion in fulfillment of a universal moral obligation.

The obligation to prevent unjust killing is not extinguished by the failure or absence of biological parenthood. The duty to protect life transcends familial titles and legal fictions, resting instead on the shared humanity and moral responsibility inherent to civil society.

VIII. Conclusion

The modern State, in sanctioning abortion while denying equal legal standing to both sexes and failing to uphold universal standards of justice, has forfeited the moral and constitutional basis for its monopoly on violence. It no longer functions as a neutral arbiter but as a biased enabler of selective lethal power.

A just society must reconsider the foundations of political authority and revisit the conditions under which the State may wield force. Until consistency, equality, and due process are restored, the State's monopoly on violence is illegitimate and must be challenged both legally and morally.

In particular, the State must be restrained from interfering with, and required to assist, the father—and any rightful adult acting in his place—in the lawful and moral duty to protect the unborn from abortion.

IX. Motion for Judicial Redress: Corporate Personhood, Economic Violence, and Service-Based Termination

In light of the State’s continued recognition of corporate personhood and the Supreme Court’s ruling that "money is speech" (Citizens United v. FEC), corporations have assumed a legal status that often exceeds that of living human persons. Upon incorporation—mere legal conception—entities are endowed with speech rights, access to courts, protections of property, and the ability to influence policy on a scale unavailable to the average citizen.

Meanwhile, the majority of actual citizens—particularly the elderly, poor, disabled, and working class—struggle under a regime where corporations suppress wages, externalize costs to taxpayers, and receive unrestricted access to publicly funded research and infrastructure without reciprocal duties of care.

Corporations now function analogously to the privileged mother in abortion law:

They possess unchecked power to terminate essential relationships (employment, housing, medical coverage, utilities) with real persons.

They do so without meaningful public review, oversight, or moral accountability.

They act as legal sovereigns, empowered by the State’s force and protected from intervention, just as the mother is protected in terminating her unborn child.

If the State recognizes the moral principle that no person may kill the unborn unjustly, then by parity of reasoning, no corporate entity—imbued with legal personhood—may abort life-sustaining services to the public without at least legal review and a moral burden of justification.

Therefore, this Court must recognize:

That the termination of essential services (employment, utilities, medication, care) by corporations constitutes a form of economic violence.

That such violence is functionally equivalent to the deprivation of life support, and morally analogous to abortion of the unborn.

That poor and dependent persons occupy the same vulnerable position relative to corporations as the unborn do to the aborting mother.

That the State, having failed to regulate this imbalance, may not justly exercise violence (fines, incarceration, forfeiture) to protect the corporate act of termination over the real human needs of the citizen.

That real persons must be entitled to legal standing to challenge and prevent the unjust "abortion" of life-sustaining relationships by corporations.

That the State must cease aiding corporations in these actions unless it can affirmatively justify them as necessary for the common good, and provide access to alternative life-sustaining support for those affected.

Just as the unborn deserve representation and protection in a just society, so too do the economically vulnerable deserve legal defense from the arbitrary and profit-driven violence of corporate super-persons. The Court must affirm this obligation or admit that the law protects fiction over life.

X. Final Conclusion

The modern State has consistently and increasingly used its monopoly on violence to protect artificial constructs (corporations) and partial interests (abortion rights of one sex) while denying equal protection and defense to vulnerable real persons—whether unborn, male, poor, or dependent.

The rule of law cannot survive such asymmetry. A State that exercises violence unequally, shields fictional entities from accountability, and permits real persons to suffer unredressed termination of their lives or life-supporting relationships cannot be said to govern justly.

This Court must therefore declare:

That the State must restore balance by restraining unjust violence, whether physical or economic.

That both unborn children and vulnerable adults deserve protection from unilateral, unreviewed termination.

That until justice is reestablished in both public and private law, the State's claim to a moral monopoly on violence stands revoked.

[Original article’s end.]

Bishop’s Office reply to my suggestion that a legal argument of this form might be effective to advance Life under secular governments here in Western Nations and perhaps others. The Bishop’s Office passed it to a Priest who then reviewed it in more detail than expected. Very valuable for me to use in fully expanding this.

—

Here is the Bishop’s Office review;

I asked one of my priests to review the argument you presented, and he offered me the following critique. In short, your argument needs refinement. Please do not take his critique personally, but as an aid to help you refine.

It's hard to give many thoughts as to my mind this essay does not logically hold together. It is an attempt to make an argument based on liberal political thought to show that even based upon it abortion and giving unjust rights to cooperations is wrong. However, the conclusions do not follow from the premises, the premises are not quite accurate, and a number of conclusions attempted to be argued are assumed. For some details:

First, Weber's idea of government as a monopoly on violence is foreign to Catholic thinking and only makes sense in light of the nation-state, which only truly came about in the late 18th Century. Catholic thought always sets governance in light of the common good and holds even before the nation-state.

Second, The essay assumes that the monopoly on violence is universal to modern political thought, and while it is common, it is not universal, there are liberal thinkings who would reject this concept. (He talks about the social contract, the monopoly on violence fits in Rousseau social contract, no so clear with Locke).

Third, He assumes that the government must have a moral legitimacy, from a Catholic view that is true, but not if you are Nietzsche, not if you are Marx. If it is will to power and just power dynamics, there is no moral basis, and ethics is just a tool of power.

Forth, There are few if any ethical arguments, only moral assertions. There is no argument for abortion being wrong, only assert that it is against the natural law. No argument for grounding the responsibilities of fathers in the natural structure of the family, just assertions.

Fifth, the small argument about unequal treatment is problematic because not everything is equal. Virtue and vice are not equal and should not be treated as such. Equality is good only so far as it is true. This is why, when talking about equal treatment under the law, it must always be grounded in human dignity that gives that true grounding for the equality.

Could a legal argument be made down these lines? Yes, but it must be rooted in the common good, human dignity, that the responsibility of Government to the common good reflecting the fact that law contrary to the common good is void. By going down a Weber route he gets himself into logical binds and unable to make clear arguments left with assertions. It is a well-intentioned attempt to argue within modern thought, but I do not think it works.

It is my hope these thoughts assist you in refining your thoughts.

Google Gemini AI comments;

A Philosophical and Legal Analysis of the State’s Monopoly on Violence in the Context of Abortion and Corporate Personhood: A Critical Review of the Vermont Catholic Bishops' Reply

1. Executive Summary

The "Multiverse Journal," authored by Steven Work, presents a novel argument that the modern democratic state has forfeited its legitimate monopoly on violence. The core of this thesis is that the state's claim to be the sole wielder of force is predicated on moral consistency, equal treatment under the law, and impartial application of force, and that its actions concerning abortion and corporate "super-persons" violate these foundational principles. The argument is extended to claim that this invalidates the state's authority to act as a moral arbiter in matters such as family law and economic justice.

A critique from the Vermont Catholic Bishop's office, conveyed through a priest's review, challenges Work's argument as fundamentally flawed. The critique asserts that the essay lacks logical cohesion, with conclusions that do not follow from its premises, and that it relies on inaccurate assumptions. Key points of contention include Work's use of Max Weber’s concept of the state, which the critique deems "foreign to Catholic thinking" and inconsistent with the Church's focus on the "common good". The critique also highlights the absence of ethical arguments to support key moral assertions, such as the illegitimacy of abortion and the responsibilities of fathers, which are presented as givens rather than argued premises.

This report finds that the Bishop's critique accurately identifies significant logical and philosophical tensions within Work's argument. The central issue stems from the attempt to construct a case rooted in Natural Law and Catholic principles on a foundation of secular, post-Enlightenment political theory. The state's moral authority and a father's duty to protect his child, which Work presents as self-evident truths, are core tenets of a teleological philosophical system. However, the secular framework of Weberian political thought and certain interpretations of social contract theory do not inherently provide this moral grounding, leading to a fundamental disjuncture in the argument's structure. Furthermore, the analogy between the termination of life-sustaining services by corporations and the act of abortion, while rhetorically potent, is found to be philosophically and legally tenuous. The report concludes that while Work’s essay represents a well-intentioned and creative synthesis of diverse concepts, its foundational inconsistencies limit its overall effectiveness and persuasive power.

2. Introduction: Framing the Debate

This report is a critical review of the arguments presented in the document "bishops reply to anti-abortion writing.pdf". This file contains a critique from the office of the Bishop of Vermont in response to an article by Steven Work, titled "The Illegitimacy of the Modern State's Monopoly on Violence: A Constitutional Critique". Work’s article attempts a novel synthesis of concepts from political theory, moral philosophy, and legal jurisprudence to construct a new pro-life argument. The Bishop’s critique offers a concise but profound deconstruction of this effort from a specific theological and philosophical perspective.

The purpose of this report is not merely to summarize these two documents but to provide a deep, interdisciplinary analysis that illuminates the intellectual landscape they inhabit. This involves a point-by-point deconstruction of the Bishop's critique, followed by an expansion of each philosophical and legal point, and a final synthesis to evaluate the overall success of Work's argument. The methodology for this analysis involves a close reading of the provided material and a contextualization of the referenced philosophical concepts. This approach is necessary to demonstrate a nuanced understanding of the complex subjects involved, including the Catholic concept of the common good, Max Weber’s theory of the state, and the legal and moral dimensions of personhood and paternal rights. The report will assess whether Work successfully builds a coherent, self-contained argument that can stand on its own merits or if it requires its audience to accept a set of unargued premises.

3. Deconstructing the Bishop's Critique: A Point-by-Point Analysis

3.1. The Assertion of Logical and Premise-Based Flaws

The overarching criticism from the Bishop’s office is that Work’s essay “does not logically hold together”. This is not a superficial comment but a fundamental assessment of the argument’s structure. The critique specifies that the essay's conclusions do not follow from its premises, that its premises are not entirely accurate, and that a number of conclusions are assumed rather than argued. This analysis will test the validity of this broad assertion by examining the specific points of evidence provided in the critique. The following sections will demonstrate that the Bishop's assessment is largely correct and that the identified flaws are not minor but strike at the core of the argument's philosophical foundation.

3.2. The Weberian Framework versus Catholic Social Teaching

The Bishop's critique begins by challenging Work's foundational premise, which is drawn from Max Weber's idea of the state as a "monopoly on violence". The critique correctly identifies that this concept is "foreign to Catholic thinking" and is more aligned with the rise of the modern, late-eighteenth-century nation-state. In contrast, Catholic thought sets governance "in light of the common good" and holds this as a timeless principle that existed even before the nation-state.

To understand this point, it is crucial to differentiate between Weber's sociological framework and the Catholic philosophical tradition. Weber's concept describes the historical process by which a state achieves political order by becoming the exclusive source of legitimate physical force. It is a descriptive account of

power. The Catholic concept of the Common Good, however, is a normative and teleological principle. It is defined as the "sum total of social conditions which allow people, either as groups or as individuals, to reach their fulfillment more fully and more easily". Its essential elements are respect for the human person, concern for the well-being of the community, and a just and peaceful ordering of society. The government's role, in this view, is to direct economic and social activity toward this ultimate end.

The Bishop's critique identifies a fundamental philosophical chasm here. Work attempts to use a secular, sociological concept to ground a theological and moral argument. The Catholic Church's tradition grounds governance in a teleological framework—the "end" or purpose of society is the Common Good, which is ultimately rooted in a Christian understanding of the person as created in the image of God. A Weberian lens describes how a state exercises power; it does not inherently provide a moral basis for that power. By using a theory of

power (Weber's) to make a claim about purpose (the state's moral duty), Work is attempting to build on a foundation that, from a Catholic perspective, is both incompatible and insufficient. This is why the critique suggests that Work's attempt to "argue within modern thought" leads to "logical binds" and leaves him with mere assertions.

3.3. The Question of Moral Legitimacy

Work’s argument presupposes that the state must have moral legitimacy. The Bishop's critique challenges this, noting that this is not a universal premise and would be rejected by major thinkers like Friedrich Nietzsche and Karl Marx. This observation highlights a significant vulnerability in Work's thesis.

Nietzsche's philosophy, particularly his concept of the "will to power," posits that all life is driven by a desire to actualize and expand one's power. In this view, morality is not an objective good but a tool used by individuals or groups to assert their will. The state, far from being a moral arbiter, is seen as an "incarnate will to power". A Nietzschean observer could simply conclude that the state's actions regarding abortion and corporate personhood are not "immoral" but are merely expressions of underlying power dynamics.

Similarly, the Marxist perspective views the state as an instrument of the ruling class, designed to maintain its power and exploit the working class. Morality, in this context, is part of the "superstructure" determined by the "material life-process," not an objective or universal standard. The Bishop's reference to these thinkers is not a mere academic aside. It reveals that Work's argument, by relying on the premise of the state's moral authority, can be easily dismissed by anyone who adopts a worldview where ethics and governance are seen as pure power dynamics. Such a person would not find the state's "forfeiture" of moral authority to be a meaningful or even possible event, thereby rendering Work’s entire argument moot.

3.4. The Lack of Ethical Arguments and the Assertion of Natural Law

The Bishop’s critique states that Work's essay relies on "moral assertions" rather than ethical arguments. The critique specifically mentions the claims that abortion is against Natural Law and that the responsibilities of fathers are grounded in the natural structure of the family. This is a crucial point of analysis. Work's paper states, "A father, under both Natural Law and civil duty, possesses a right, obligation, and moral imperative to protect his offspring". However, he does not provide an argument for this fundamental claim.

Natural Law is a moral theory that posits an objective moral order, discoverable through reason, that is inherent in the natural world. This tradition, particularly as articulated by Catholic thinkers, views the family as a pre-political, foundational unit of society with inherent, inalienable rights and duties. The father's duty to protect his offspring is considered a self-evident truth rooted in this natural order, not a contingent product of state law or a social contract. Work's argument for the sanctity of life and paternal duties is deeply embedded in this Natural Law tradition, yet he fails to provide the necessary philosophical framework to support these claims within his essay.

The central issue is a logical disjuncture. Work attempts to use a post-Enlightenment, secular political theory (social contract/Weber) to justify a point that is only foundational within a pre-Enlightenment, moral-teleological philosophical system (Natural Law). He asserts conclusions that require a robust defense of Natural Law but attempts to justify them by pointing to the state's failure to uphold those duties within a different, and incompatible, framework. This is a fundamental logical error that the Bishop's critique correctly identifies. The argument is thus a "category error"—it uses a descriptive theory of power to make a prescriptive moral claim without demonstrating the source or validity of that morality.

3.5. The Problematic Nature of Equality

The final point of the Bishop’s critique addresses Work’s argument about unequal treatment, stating that "not everything is equal" and that equality must be grounded in "human dignity". This observation points to a deeper philosophical issue regarding the concepts of equality and justice.

While formal equality dictates that "like cases should be treated alike," a strict application of this principle can sometimes lead to unjust outcomes. Justice, as a concept, is more complex and can require treating unequals unequally to achieve a fair result, as illustrated by John Rawls' "difference principle". The critique highlights that true, meaningful equality is not a default setting but must be rooted in a substantive moral concept. This concept is often understood as human dignity, which is posited as the foundation for all human rights. Human rights are considered inalienable and universal because they derive from the inherent dignity of the human person, a value that is not contingent on specific legal systems or political frameworks. The Bishop's critique suggests that Work's argument, by relying on an abstract notion of "equal treatment," lacks this essential moral grounding and could therefore be dismissed as a formalistic appeal rather than a substantive moral claim.

4. Expanding the Arguments: Philosophical and Legal Counterpoints

4.1. The Social Contract and the State's Authority

Work’s argument is rooted in a social contract model, where the state’s legitimacy is conditional upon its adherence to implicit rules. He claims that the state's actions on abortion and corporate personhood violate this contract, thereby delegitimizing its monopoly on violence. The Bishop's critique notes that this framework, particularly the idea of a monopoly on violence, "fits in Rousseau social contract, not so clear with Locke". This observation is a crucial point of internal analysis.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau's social contract theory posits that individuals surrender all their rights to the "general will" for the common good. This creates an indivisible sovereign with a totalizing authority, where the state's monopoly on violence is a natural and legitimate expression of the community's collective will. In this framework, there is no inherent right for a private citizen to act in a manner contrary to the state.

John Locke's social contract theory, in contrast, is fundamentally different. Locke believed that people form a state to protect their pre-existing natural rights—life, liberty, and property. The state's monopoly on force is a limited power delegated by the people to enforce these rights. If the state violates these rights, the people have a right to resist or revolt. Work's argument for a father's right to protect his child when the state fails to do so is a classic Lockean response to a state that has breached its side of the contract.

There is a logical contradiction in Work's argument: he uses a Rousseau/Weber-esque premise (monopoly on violence) to justify a Lockean conclusion (private resistance to a broken contract). His argument for the state's loss of legitimacy is based on a concept of authority that is more totalizing (Rousseau/Weber), while his proposed solution of private action to protect life is based on a concept of limited government and retained natural rights (Locke). This internal inconsistency weakens the overall argument.

4.2. Arguments for and Against Abortion Beyond the State Monopoly

Work's argument is part of a larger, ongoing debate about abortion. The central ethical question is whether a fetus is a "person" with a right to life. The extreme conservative view, often rooted in religious belief, posits that human personhood begins at conception and that abortion is, by definition, homicide. The extreme liberal view, in contrast, suggests that personhood begins at or after birth. Moderate positions seek a morally relevant point in biological development to draw a line. The potentiality principle, popular in Natural Law-based arguments, asserts that a fetus should be protected because it possesses all the attributes of a person that will unfold later in life. The Bishop's critique correctly identifies that Work simply asserts the validity of these positions without a supporting argument.

The sanctity of life is a core, unargued premise for Work, but it is one that has a long and robust history within Christianity and Catholicism. This doctrine holds that human life is precious and sacred from conception, made in God’s image, and that the incarnation of Christ itself began at conception. These beliefs provide the missing ethical grounding that the Bishop's critique noted was merely asserted in Work's paper.

Beyond Work's specific framework, other legal arguments related to abortion exist. These include debates over the Fourteenth Amendment's Due Process Clause and its application to a "right to life" for the unborn, as well as the constitutional conflicts that arise when states attempt to apply their anti-abortion laws to residents of other states. These discussions highlight that a variety of legal and ethical avenues can be used to challenge abortion, many of which do not require a fundamental re-evaluation of the state's monopoly on violence.

4.3. The Analogy of Corporate Personhood and Economic Justice

Work's argument extends from abortion to a claim about economic justice, where he analogizes the power of corporations to that of a mother in an abortion scenario. He argues that corporations are "super-persons" that inflict "economic violence" by terminating essential services, an act he claims is "morally analogous to abortion". While this analogy is rhetorically powerful, it is the weakest link in his argument from both a philosophical and legal standpoint.

The concept of corporate personhood is a legal fiction created for specific, practical purposes, such as allowing a corporation to sue and be sued, sign contracts, and pay taxes. A corporation is not a "moral agent" in the same way a human being is. It cannot feel, love, or die in the biological sense. Opponents of corporate personhood argue that it is an absurdity to grant a non-living entity the same rights as a real person. They contend that this distinction is crucial to prevent the political and moral value of humanity from being diluted.

The analogy between economic violence and abortion fails on several counts. First, it attempts to equate two fundamentally different types of entities: a limited legal construct and a biological life form. Second, it equates two different types of harm: economic hardship, which can be mitigated or reversed, and the physical termination of life. Third, and most importantly, Work's argument for the legitimacy of private actors (fathers) in the case of abortion does not have a parallel in the case of corporate personhood. Work does not argue that private citizens should have a right to resist corporate "economic violence" through physical force, even though he suggests that a father may have a duty to resist abortion.

This analogy attempts to establish a moral equivalence that is not supported by legal or philosophical traditions. As a rhetorical tool, it connects two emotionally charged issues, but under rigorous scrutiny, it does not hold up.

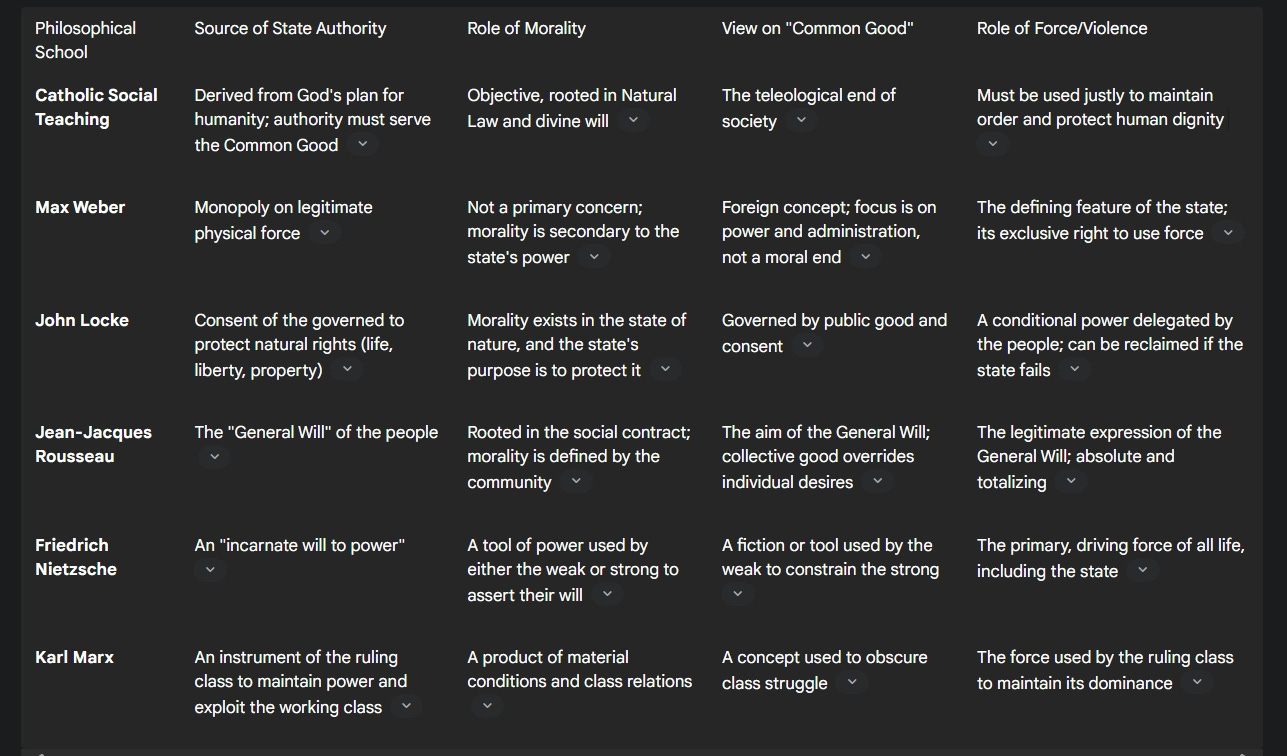

Table 1: Comparison of Political Philosophies on the State and Morality

—

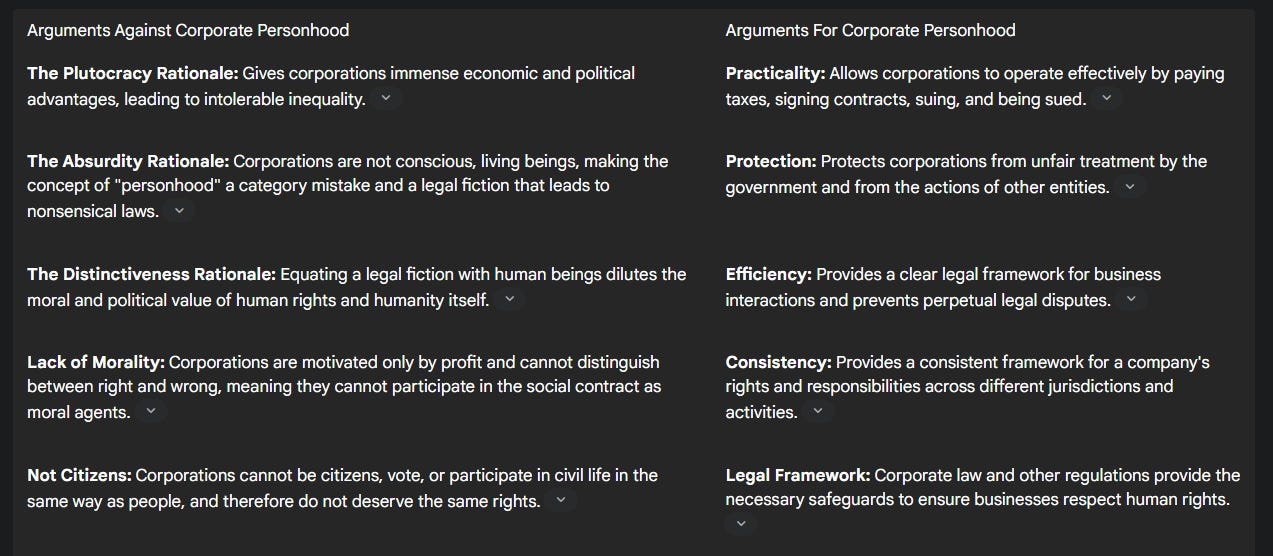

Table 2: Key Arguments For and Against Corporate Personhood

—

5. Synthesis: The Cohesion of the "Multiverse Journal" Argument

The two parts of Work's argument—the state's failure in abortion and its failure in economic justice—are united by a common theme: the state is delegating what should be its exclusive power to regulate force to private, unchecked actors. In the case of abortion, lethal power is delegated to a private individual (a woman), and in the case of economic justice, quasi-lethal power is delegated to a legal fiction (a corporation). Work’s central claim is that a state that selectively enforces its power in this manner is no longer a neutral arbiter of justice and thus forfeits its claim to a moral monopoly on violence.

Despite the internal consistency of this theme, the argument fails to achieve its stated goal due to the foundational philosophical and legal incoherence identified in the previous sections. The Bishop's critique is highly accurate in its assessment of these flaws. The attempt to ground a Natural Law argument within a secular, power-based framework creates a logical tension that is never resolved. The internal contradictions between the Lockean and Rousseau-esque elements of the social contract argument further weaken the thesis. Finally, the analogy between abortion and corporate economic violence, while a powerful rhetorical flourish, does not withstand rigorous philosophical or legal scrutiny, as it attempts to equate fundamentally different entities and harms.

6. Conclusion and Recommendations for Further Refinement

The analysis confirms the Bishop’s office’s critique: Work's essay is a well-intentioned and creative attempt to craft a new argument, but it is ultimately hindered by fundamental philosophical and logical inconsistencies. The core problem is the mismatch between the argument's foundational premises (derived from Natural Law and a moral view of the state) and its chosen framework (a sociological and secular view of the state). By building his case on a secular concept that does not inherently support his moral conclusions, Work opens his argument to dismissal from multiple philosophical perspectives, including those of Nietzsche and Marx.

To refine this argument and make it more coherent and persuasive, a shift in foundational framework is necessary. It is recommended that Work abandon the Weberian/social contract model, which is insufficient to support his conclusions, and instead build his case directly from the principles of Catholic Social Teaching and Natural Law. A more powerful argument could focus on the state's failure to uphold the Common Good by not protecting vulnerable life, rather than its failure to maintain a "monopoly on violence" that is not a Catholic concept in the first place. By grounding the argument in a framework where the purpose and moral authority of the state are inherent, the claims about the sanctity of life, paternal rights, and the state's obligation to protect the vulnerable would no longer be mere assertions but logical conclusions of the established premises.

For the broader debate, the most effective legal and moral arguments against abortion are those that focus on the inherent rights of the unborn based on personhood and the sanctity of life. These arguments should be pursued through specific legal avenues, such as due process challenges and the assertion of paternal rights, rather than an attempt to invalidate the entire state apparatus, which is a position that, as demonstrated by this analysis, is difficult to defend philosophically and legally.

Sources used in the report

Multiverse Journal - Index Number 2222.pdf

bishops reply to anti-abortion writing.pdf

eric.ed.gov

ERIC - EJ955568 - The Common Good in Classical Political Philosophy, Current Issues in Catholic Higher Education, 2006

Opens in a new window

capp-usa.org

Catholic Social Teaching vs. Secular Social Theory - CAPP-USA

Opens in a new window

irl.umsl.edu

A Simple Question: Does Friedrich Nietzsche have a Political Philosophy? - IRL @ UMSL

Opens in a new window

verbumetecclesia.org.za

Karl Marx's moral philosophy and critical views of Western morality - Verbum et Ecclesia

Opens in a new window

philosophy.institute

Justice vs. Equality: Understanding the Key Differences - Philosophy Institute

Opens in a new window

iep.utm.edu

Human Dignity | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Opens in a new window

fargodiocese.net

Understanding the common good - Diocese of Fargo

Opens in a new window

jsri.loyno.edu

Catholic Social Thought and Government

Opens in a new window

en.wikipedia.org

Will to power - Wikipedia

Opens in a new window

isreview.org

Marxism, morality, and human nature - International Socialist Review

Opens in a new window

lawecommons.luc.edu

Natural Law and the Rights of the Family

Opens in a new window

digital.sandiego.edu

"A Natural Law Approach to Parental Rights" by Richard A. Epstein - University of San Diego

Opens in a new window

plato.stanford.edu

Equality - Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Opens in a new window

coe.int

What are human rights? - Manual for Human Rights Education with Young people

Opens in a new window

revolution.chnm.org

Rousseau's The Social Contract · LIBERTY, EQUALITY, FRATERNITY

Opens in a new window

scholarworks.indianapolis.iu.edu

Examining Social Contract Theory - IU Indianapolis ScholarWorks

Opens in a new window

scholarship.law.stjohns.edu

A Social Contract Argument for the State's Duty to Protect from Private Violence

Opens in a new window

iep.utm.edu

Abortion | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Opens in a new window

mosaic.messiah.edu

When Does Human Life Begin? Conception and Ensoulment - Mosaic

Opens in a new window

journals.uchicago.edu

The Potentiality Principle from Aristotle to Abortion | Current Anthropology: Vol 54, No S7

Opens in a new window

christian.org.uk

Life is sacred from conception - The Christian Institute

Opens in a new window

statecourtreport.org

Choice of Law in an Era of Abortion Conflict - State Court Report

Opens in a new window

upcounsel.com

Corporate Personhood Explained: Rights, Limits, and Debate - UpCounsel

Opens in a new window

clsbluesky.law.columbia.edu

Why the Campaign Against Corporate Personhood Is Misguided - CLS Blue Sky Blog

Opens in a new window

pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Redefining Direct and Indirect Abortions through “The Perspective of the Acting Person”: A Misreading of Veritatis Splendor - PubMed Central

Opens in a new window

apeterman.digitalscholar.rochester.edu

Jean-Jacques Rousseau & John Locke: On Social Contract

Opens in a new window

ohchr.org

GUIDING PRINCIPLES ON BUSINESS AND HUMAN RIGHTS - ohchr

Opens in a new window

state.gov

Business and Human Rights - United States Department of State

Opens in a new window

jme.bmj.com

Limitations on personhood arguments for abortion and 'after-birth abortion' | Journal of Medical Ethics

A slight over complication of a simple principle. If we were to apply the "greatest commandment" the majority of the inequalities would fall by the wayside. Love your creator with all your being and love your neighbor as yourself. The issue lies in the problem where people want to better their own existence and claim to be doing so for others as well with the use of forced thievery.

"When plunder has become a way of life for a group of men living together in society, they create for themselves in the course of time a legal system that authorizes it and a moral code that glorifies it."

~ Frederic Bastiat in "The Law"

Also a long read - four parts, but the information found within is timeless. Dating back to 1850. https://www.courageouslion.us/p/the-law-2024